Walking the Socratic Trail: Exploring Ancient Athens' Philosophical Landmarks

As someone who has spent years immersed in the study of ancient history and philosophy, I’ve often found myself retracing the steps of the great thinkers who shaped Western thought. One afternoon, standing amidst the ruins of the Ancient Agora, it struck me that this wasn’t just a space of monuments, but the very heartbeat of Athenian intellectual life. What if visitors could walk in the footsteps of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, not just as tourists, but as seekers of wisdom?

That’s how I came up with the Socratic Trail — a personal journey, a philosophical pilgrimage through the city that gave birth to democracy and some of the most profound ideas in human history. The idea is simple: to follow the paths of the ancient philosophers, exploring not only the sites but the questions that made them legendary. For those passionate about philosophy, this isn’t just a tour; it’s an intellectual exploration of the very ground that nurtured the foundations of our thought. Athens is alive with history, but for those willing to look deeper, it’s also alive with philosophy.

Join me on this trail — where we walk not just to see, but to think.

First Stop: The Ancient Agora – The Cradle of Socratic Philosophy

Welcome to the Ancient Agora, where the pulse of Athens once beat and where philosophical debates shaped the intellectual foundation of the Western world. As I walk with you today, let me guide you through this storied space, where Socrates himself once roamed. For any philosophy enthusiast, the Agora is not just a historical site—it is a living testament to the philosophical inquiry that defined Athens in its golden age.

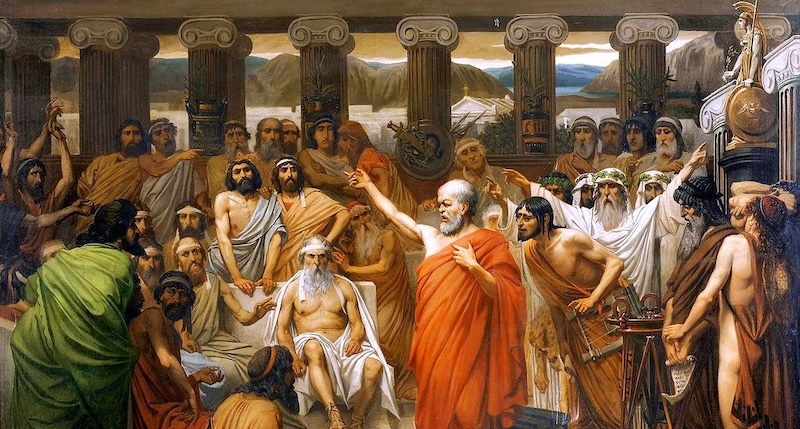

The Agora, situated at the foot of the Acropolis, served as the center of political, social, and intellectual life in ancient Athens. In the 5th century BCE, it was here that Athenians gathered to discuss everything from politics to ethics. While it was filled with market stalls and bustling crowds, the Agora was equally a hub for philosophical discussions, with Socrates at the heart of many of these conversations. Socrates wandered through this very space, stopping citizens to question their beliefs and ignite deep intellectual debates. The Agora is, without a doubt, where the Socratic method came to life.

Stoa Poikile – The Painted Stoa of Stoic and Socratic Debate

One of the essential stops for any philosopher buff is the Stoa Poikile or the Painted Stoa. Though the remnants may seem modest now, this structure once boasted elaborate frescoes depicting scenes of Athenian victories and mythical battles. However, for us, it is what happened here that truly matters.

While this stoa later became the birthplace of Stoicism, founded by Zeno of Citium, it was also a place where Socrates often lingered. Socrates didn’t formally teach like the philosophers that came after him, but he engaged in public discussions here, often challenging prominent thinkers and average citizens alike. Imagine Socrates standing right here, challenging Athenians on the nature of virtue, justice, and knowledge.

The Bouleuterion – Where Democracy and Philosophy Intersected

Not far from the Painted Stoa is the Bouleuterion, the council chamber where the 500-member council of Athens would meet. Socrates wasn’t just a philosopher living on the fringes—his ideas often intersected with the political currents of the day. It’s here, in the political heart of Athens, where philosophy and democracy collided.

Socrates’ philosophical inquiry often put him at odds with the political elite, which eventually led to his trial. While Socrates never directly participated in Athenian politics, his philosophy heavily influenced democratic ideals and ethics. Walking through the ruins of the Bouleuterion, you can almost feel the tension between political power and philosophical inquiry—a tension that would culminate in Socrates’ ultimate fate.

The Heliaia – The Courtroom of Socrates’ Trial

As we continue through the Agora, we reach the site of the Heliaia, one of Athens’ largest courts. This is where Socrates was tried and condemned in 399 BCE for “corrupting the youth” and introducing strange gods. For philosophy buffs, this place holds special significance—it’s where philosophy was put on trial.

Socrates defended himself not by appealing to the court but by remaining true to his principles. He believed that philosophy, the pursuit of truth, was more valuable than life itself. Standing here, you can reflect on the gravity of that moment—a moment when philosophy, for the first time in history, clashed head-on with the state.

The Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios – A Reflection on Freedom

Just beyond the Heliaia is the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios. This was not just a stoa dedicated to Zeus, the god of freedom, but also a place where philosophers gathered to discuss freedom in all its forms—political, ethical, and intellectual. For Socrates, freedom wasn’t just a political ideal; it was a moral imperative. His relentless questioning was, in many ways, a pursuit of intellectual freedom—freedom from ignorance, from falsehood, and from the constraints of unexamined beliefs.

As you walk through this space, consider Socrates’ unique approach to freedom. He didn’t preach liberty in the political sense but sought a deeper freedom—the freedom that comes from understanding oneself and one’s place in the world.

Second Stop: Plato’s Academy – Walking in the Footsteps of Great Minds

After the lively discussions of the Agora, our next destination takes us to a quieter but no less important site: Plato’s Academy. Founded by Plato in 387 BCE, the Academy was more than just a school; it was the birthplace of Western philosophy and one of the most influential intellectual centers of the ancient world. Located in the northwest of the city, this area, known as Akademeia, once housed sacred groves dedicated to Athena, where Plato gathered students to engage in dialogues that would shape Western thought for centuries to come.

The physical remains of Plato’s Academy are not as visually imposing as those of the Acropolis or the Agora, but they hold immense historical value. Excavations, which began in the early 20th century, have revealed key structures such as a gymnasium and a palaestra, used for physical training, alongside the philosophical discussions that took place in these peaceful surroundings. The site also contains foundations of large buildings, including possible lecture halls where Plato and his successors would have taught. These remains underscore the balance of mind and body that was central to Greek education.

Although the Academy’s ruins are sparse, the significance of what transpired here cannot be overstated. In this intellectual haven, Plato composed his most famous works, including “The Republic,” where he discussed his vision of an ideal society ruled by philosopher-kings. His method of teaching, known as dialectic, encouraged students to question, debate, and engage in the search for truth—a practice that continues to influence modern educational systems.

The Academy was situated outside the city walls, in what was once a sacred olive grove. The choice of location reflects the philosophical ideal of withdrawal from the noise and distractions of public life to focus on higher learning. Yet, Plato’s philosophy was deeply connected to the city’s political and social life. Many of his students, including Aristotle, would go on to play significant roles in shaping political theory, ethics, and science.

While the Academy was a place for philosophical exploration, it was also a political space. Plato’s ideas on justice, governance, and the role of the philosopher in society were profoundly influenced by the political turmoil of Athens during his lifetime. Plato’s Academy thus became a refuge where philosophical thought could flourish, free from the constraints of the Athenian democracy, which had condemned his mentor, Socrates.

Plato’s Academy remained active for almost 900 years, well into the Roman period. His student Aristotle, who later founded his own school, the Lyceum, built upon Plato’s teachings while offering new perspectives on logic, science, and ethics. The Academy’s influence extended far beyond Athens, shaping the intellectual traditions of the Roman Empire and, later, the Renaissance.

For the modern visitor, walking through the quiet grove of the Academy offers a reflective experience. Though the buildings are long gone, the spirit of philosophical inquiry that Plato instilled here lives on. It’s a place to pause, think, and engage with the ideas that have shaped the very foundations of Western thought.

Third Stop: Aristotle’s Lyceum – The Birthplace of Systematic Thought

The next significant stop on our philosophical journey is Aristotle’s Lyceum, a site of immense historical importance in ancient Athens. Discovered in 1996 during construction work near Syntagma Square, this once-hidden gem now offers visitors a tangible connection to the intellectual legacy of Aristotle. Established around 335 BCE, the Lyceum was not just a philosophical school but a center for scientific study, where Aristotle developed his methods of inquiry and observation that laid the foundation for much of Western intellectual tradition.

The site was uncovered during modern excavations and revealed the foundations of a large complex. Archaeologists identified a gymnasium, palaestra, and gardens, which were typical features of a Greek educational institution. The Lyceum, like other similar sites, would have had spaces for both intellectual discussions and physical exercise—an embodiment of the Greek belief in balancing mind and body.

The remains, though modest, include a series of rectangular buildings, open courtyards, and exercise grounds, all essential to the daily life of Aristotle’s school. Here, Aristotle and his students would have engaged in conversations and lectures, while also conducting studies in various disciplines ranging from biology to politics. The discovery of these architectural elements has helped scholars better understand the layout and functions of ancient philosophical schools.

Aristotle, a student of Plato, founded the Lyceum as an institution of learning that diverged from his teacher’s focus on ideal forms. Instead, Aristotle grounded his philosophy in the empirical study of the natural world. The Peripatetic School, named after the Greek word “peripatos” (meaning “walking”), was known for Aristotle’s practice of teaching while walking with his students through the grounds. The Lyceum became a place where philosophy and science intersected—where Aristotle conducted some of his most important works, including treatises on ethics, logic, and biology.

This site also played a key role in the intellectual life of Athens during the Hellenistic period. The Lyceum housed one of the most extensive libraries in the ancient world, and its influence extended far beyond the lifespan of Aristotle. His successor, Theophrastus, continued to teach and develop scientific research here, contributing to the Lyceum’s status as a premier institution for philosophical and scientific inquiry.

Fourth Stop: The Pnyx – The Birthplace of Democracy and Philosophical Debate

Our next destination on the Socratic trail is The Pnyx, an often-overlooked but profoundly significant site. Nestled on a hill west of the Acropolis, the Pnyx served as the assembly point for Athenian democracy. It’s here that citizens of Athens would gather to listen to debates, vote on critical matters of state, and witness the kind of oratory and philosophical exchange that helped shape the intellectual life of ancient Athens. The Pnyx, more than any other place, represents the intersection of philosophy and politics.

Excavations of the Pnyx began in the early 20th century, uncovering a large, open-air auditorium carved into the rock of the hillside. This assembly area could accommodate up to 6,000 citizens, making it the literal and symbolic foundation of Athenian democracy. The excavations revealed three distinct phases of the Pnyx’s development. The first phase (6th century BCE) was a rudimentary gathering space. The second phase, during the 5th century BCE, saw the construction of a larger, more formalized assembly area, with steps and speaker’s platforms. The third and final phase (4th century BCE) expanded the site to its largest capacity, reflecting the growing importance of democratic participation in Athenian society.

The most prominent feature is the Bema, a raised stone platform from which prominent speakers, including Pericles and Demosthenes, addressed the assembly. It’s possible to stand on this very platform today, imagining the passionate political and philosophical debates that once reverberated across this hilltop. For philosophers, especially Socrates and his followers, this was a vital space—not just for political engagement but for testing and challenging ideas through public discourse.

The Pnyx wasn’t merely a political stage; it was also a venue for the philosophical questioning of political power and ethics. Socrates, although not a politician himself, was often critical of the democratic process, questioning whether the masses could be trusted to make wise decisions without proper philosophical guidance. His teachings at the Agora and beyond indirectly challenged the very democratic ideals that were born here. Plato, in his famous work The Republic, argued that only philosopher-kings were fit to rule, a direct critique of the democratic practices that unfolded at the Pnyx.

Yet, the Pnyx also embodies the Athenian belief in the power of speech, reason, and debate—the same principles that are at the heart of philosophical inquiry. For modern visitors, standing at the Pnyx offers a chance to reflect on the long history of democratic participation and how closely it is tied to the development of philosophical thought.

Today, the Pnyx remains a quiet and less visited site, but it offers some of the best views of Athens, including a breathtaking panorama of the Acropolis. It is an ideal place for visitors to reflect on the philosophical debates that took place here and to appreciate the historical significance of a space where the practice of free speech began.

Fifth Stop: The Areopagus – The Hill of Trials and Philosophical Debates

The next point on our Socratic trail is the Areopagus, a rocky hill located northwest of the Acropolis. The Areopagus holds a special place in both the political and philosophical history of Athens. In ancient times, it served as the seat of the highest judicial council, the Council of the Areopagus, which handled serious crimes like murder, treason, and religious impiety. But beyond its legal significance, the Areopagus was also a place where new ideas and philosophical debates were introduced and contested.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Areopagus was used as a meeting place as early as the Bronze Age. The council that met here was one of the oldest institutions in Athens, predating the democratic reforms of the Classical period. The hill itself bears the marks of its judicial past, with cut steps and seating carved directly into the rock, where the council members and the public would have gathered.

The council was originally composed of former archons (magistrates), and its power diminished with the rise of democracy in the 5th century BCE, when the democratic Heliaia court began to handle most legal matters. However, the Areopagus retained authority over cases involving religion and homicide, which meant it continued to play a crucial role in the moral and philosophical life of Athens.

The Areopagus is closely linked with one of the most famous episodes in Athenian philosophical history—the trial of Socrates. While the trial itself took place in the Heliaia, the Areopagus was the embodiment of the old legal and moral order that Socrates challenged through his teachings. Socrates’ questioning of traditional values and the Athenian gods was perceived as a threat to the city’s moral fabric, and his trial and subsequent execution in 399 BCE became a defining moment in the intersection of law, politics, and philosophy.

One of the most significant philosophical moments to take place on the Areopagus came several centuries after Socrates, when the Apostle St. Paul delivered his famous sermon here in the 1st century CE. Standing on the Areopagus, Paul spoke to the Athenians about the “unknown god” they worshipped, attempting to bridge the gap between Greek philosophy and Christian theology.

Paul’s speech, recounted in the Acts of the Apostles, is one of the earliest recorded moments where Christianity engaged directly with Greek philosophical thought. The Areopagus, therefore, became a meeting point for two of the most influential philosophical traditions—Greek rationalism and Christian theology. This fusion of ideas is a testament to the ongoing relevance of the Areopagus in the philosophical history of Athens.

Today, the Areopagus is a peaceful site, often overlooked by tourists, but it offers some of the best views of the Acropolis and the city of Athens. Visitors can climb the hill to stand where both Socrates’ legacy and St. Paul’s teachings left their mark on history. The rough-hewn steps and the stone surface bear silent witness to the many philosophical and legal debates that took place here.

Sixth Stop: The Acropolis – The Symbol of Athenian Greatness and Philosophical Reflection

The Acropolis of Athens is not only the most iconic landmark of ancient Greece but also a profound symbol of the intellectual and philosophical heights that the city reached. Standing atop the limestone hill, the Acropolis has witnessed the unfolding of Athenian democracy, culture, and philosophy, and offers an excellent vantage point from which to reflect on the philosophical ideals that emerged in this city.

The Acropolis, crowned by the Parthenon, was the religious and cultural center of Athens. Built in the 5th century BCE under Pericles, the Parthenon and the other structures atop the Acropolis represent the zenith of Athenian art, culture, and philosophy. The architecture of the Parthenon, with its harmonious proportions and balance, reflects the ideals of order, reason, and beauty—principles that are also at the core of Greek philosophy.

Philosophers like Plato and Aristotle often referred to the Parthenon and the Acropolis as the epitome of the harmony between human reason and divine order. The construction of the Acropolis coincided with the flourishing of Socratic and Sophist philosophy, and it was seen as a manifestation of Athenian values—democracy, rationality, and civic duty.

The Theatre of Dionysus – A Philosophical Stage

On the southern slopes of the Acropolis lies the Theatre of Dionysus, the birthplace of Greek drama and a critical site for the intersection of philosophy and art. It was here that Aristophanes’ play “The Clouds” was performed, a satirical work that critiqued Socrates and the Sophists. In this play, Socrates is caricatured as a thinker disconnected from practical life, engaging in absurd thought experiments. The portrayal, though exaggerated, illustrates how the Athenians viewed philosophy with a mixture of reverence and skepticism.

The theatre also hosted tragedies by Sophocles, Euripides, and Aeschylus, whose works were often infused with deep philosophical questions about fate, justice, and the nature of human existence. For a philosopher, visiting the Theatre of Dionysus is an opportunity to reflect on how performance and philosophical discourse intertwined in the cultural life of Athens.

The Prison of Socrates

Though not officially recognized as such, a cave near the base of the Acropolis on Philopappos Hill is traditionally believed to be the Prison of Socrates, where the philosopher was held after being sentenced to death for corrupting the youth and impiety. This site is particularly poignant for philosophy enthusiasts, as it represents the tragic end of Socrates’ life—a man who stood by his beliefs and accepted the will of the state, even at the cost of his life.

Connecting the Dots: Philosophy’s Living Legacy in Athens

Athens isn’t just an ancient city of stones and ruins—it’s a living testament to the evolution of human thought. To walk the Socratic Trail is to witness how philosophical ideas, born centuries ago, continue to resonate with and challenge modern society. In a world often dominated by fast-paced, surface-level interactions, the journey through the Agora, Plato’s Academy, Aristotle’s Lyceum, and the Acropolis provides a powerful contrast—a reminder of the deep, reflective thinking that once shaped entire civilizations.

When I was walking in the Ancient Agora, I realized: Socrates’ defiant questioning, in the face of an audience who valued conformity and tradition, set the stage for philosophy’s role as a disruptive force. His trial, which took place here, marked a profound tension between individual conscience and societal norms—a struggle that still echoes in contemporary debates on free speech and moral integrity. The Agora, in this light, serves as a timeless reminder that philosophy is not just theoretical; it is deeply entwined with the responsibilities and risks of public life. Today, we see Socrates’ legacy in every individual who dares to question the status quo, to speak truth in challenging times.

Then, when I moved to Plato’s Academy, I couldn’t stop thinking how materealistic we have all became. Plato’s conviction that beyond the visible world lies a realm of unchanging ideas, challenges me to think beyond the material distractions of modern life. In a world obsessed with consumerism and instant gratification, Plato’s teachings remind me of the deeper, more meaningful realities that can be accessed through reason and contemplation. Standing where the Academy once flourished, visitors can feel the weight of this intellectual tradition — a tradition that calls us to seek higher ideals, to question not just the world around us but also the essence of truth, beauty, and justice.

At Aristotle’s Lyceum, philosophy returns to the world of empirical observation and grounded inquiry. Aristotle, walking with his students through the grounds, embodied a balance that is strikingly relevant today: the harmony between thought and action, theory and practice. His teachings on ethics, politics, and science not only shaped the intellectual landscape of his time but also laid the foundation for modern disciplines like biology, political theory, and even psychology. Aristotle’s method of examining the natural world through observation mirrors today’s scientific approach, showing that ancient philosophy was not abstract or disconnected but deeply engaged with the realities of life. His Lyceum, with its focus on practical wisdom, offers a striking model for integrating philosophical thought into everyday decision-making.

It took me a while to realize that philosophy can be practical and I can apply it to guide my every-day way of living. Of course, the modern revival of Stoicism, has helped me a lot to see how these ancient teachings can guide people facing personal and collective challenges. The search for meaning, purpose, and resilience remains as relevant today as it was in ancient Athens. The Socratic Trail thus becomes more than a historical journey—it becomes a map for navigating the complexities of contemporary life, urging us to embrace the reflective wisdom of the past to solve the pressing issues of the present.

Exploring Philosophers’ Athens: Guided and Self-Guided Tours

Guided Tours for Philosophy Enthusiasts

- Athens Highlights: Myths & Philosophers Private Walking Tour This private walking tour combines Athens’ key historical landmarks with philosophical discussions, tracing the footsteps of ancient philosophers like Socrates and Plato. Visitors will explore major sites such as the Acropolis, Ancient Agora, and Pnyx Hill, while learning about their role in shaping Western philosophical thought. With a private guide, you get to immerse yourself in the city’s intellectual history, making this tour perfect for those interested in the intersection of history and philosophy.

- Philosophy Experience at Plato’s Academy Park For those wanting to delve into the teachings of Plato, this guided tour takes you through Plato’s Academy Park. While the site itself might lack the grandeur of other archaeological remains, the philosophical significance it holds makes it a must-visit for those passionate about the history of ideas. The guide not only narrates Plato’s life and teachings but also connects them to contemporary life, creating a rich, interactive experience.

- Aristotle’s Philosophy Experiential Workshop at the Lyceum If you’re intrigued by Aristotle’s philosophy, this experiential workshop held at the site of the Lyceum offers a hands-on approach to learning about his teachings. Participants walk through the grounds where Aristotle once taught while engaging in practical philosophy exercises inspired by his works. The workshop gives visitors a sense of how Aristotle’s peripatetic style of teaching influenced his philosophical ideas.

- The Great Greek Philosophers Guided Walking Tour This tour provides a comprehensive exploration of the lives and works of Greece’s greatest philosophers—Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Participants are taken to significant historical locations related to these figures while learning about their contributions to Western thought. This tour blends Athens’ rich history with philosophical insights, making it ideal for anyone who wants to explore the city from a more intellectual perspective.

Self-Guided Tours

- Ancient Agora E-Ticket & Optional Audio Tour The Ancient Agora, the heart of ancient Athenian public life, was not just a marketplace but also a center for philosophy. With this e-ticket and audio guide, visitors can explore the site where Socrates and other philosophers once engaged in debates. The tour covers significant structures, including the Stoa Poikile and the Temple of Hephaestus, offering insights into the philosophical and political life of Athens. This is perfect for philosophy enthusiasts who want to explore at their own pace.

- Acropolis and 6 Archaeological Sites Combo Ticket This combo ticket provides access to several archaeological wonders in Athens, including the Acropolis, the Ancient Agora, and the Roman Agora. It’s ideal for those who want to immerse themselves in the ancient world, where philosophy and public discourse shaped history. With the flexibility to visit seven iconic sites at your own pace, you can explore the places where Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle taught, debated, and influenced Western thought.

- Agora and Hephaistos Temple Entrance Ticket For those interested in philosophy and architecture, this self-guided tour offers direct access to the Ancient Agora and the remarkably preserved Temple of Hephaestus. The Agora was a focal point for philosophical discussions, and this tour allows you to explore its ruins while contemplating the thoughts and debates that took place there. Visitors can delve deep into the significance of these sites and their impact on the development of Western philosophy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the Agora used for in ancient Athens?

The Agora served as the central public space in ancient Athens. It was the heart of political, commercial, social, and religious life, where citizens gathered to discuss politics, shop at the markets, attend religious ceremonies, and engage in philosophical debates.

How long do you need in Ancient Agora of Athens?

You typically need around 1 to 2 hours to explore the Ancient Agora, depending on your interest level in history and archaeology. This allows time to visit key sites like the Stoa of Attalos, the Temple of Hephaestus, and the museum.

How much does it cost to go to the Ancient Agora of Athens?

The entrance fee to the Ancient Agora is included in the combined ticket for the Acropolis and several other archaeological sites in Athens. Prices may vary, so it’s best to check current rates before your visit.

Is the Ancient Agora worth visiting?

Absolutely! The Ancient Agora is a must-visit for anyone interested in ancient Greek history, philosophy, and architecture. It offers a unique insight into the daily life of ancient Athenians and the foundation of Western democracy.

What is the difference between the Acropolis and the Agora?

The Acropolis is a high city that served as the religious center of ancient Athens, home to important temples like the Parthenon. The Agora, on the other hand, was the civic center, where political, social, and commercial activities took place.

How do I get into the Ancient Agora?

The main entrance to the Ancient Agora is located at Adrianou Street, near Monastiraki Square. It’s easily accessible by metro, with Monastiraki station being the closest stop.

What are some fun facts about the Agora?

- The Agora was not only a marketplace but also the birthplace of democracy, where citizens gathered to discuss and vote on public matters.

- The Stoa of Attalos, a large covered walkway, was rebuilt in the 1950s and now houses the Museum of the Ancient Agora.

- The Temple of Hephaestus in the Agora is one of the best-preserved ancient temples in Greece.

What was Plato’s Academy in Athens?

Plato’s Academy was one of the most important centers of learning in ancient Greece. Founded by the philosopher Plato around 387 BC, it served as a place for scholars to gather, discuss, and teach philosophy, mathematics, and science.

Why is Plato’s Academy so important?

Plato’s Academy is considered the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. It played a crucial role in the development of philosophy, especially through its influence on Plato’s most famous student, Aristotle.

Can you visit Plato’s Academy?

Yes, you can visit the site where Plato’s Academy once stood in modern-day Athens. The area has been converted into a public park known as Akadimia Platonos, where you can see the remains of the ancient school.

What happened to Plato’s Academy?

Plato’s Academy continued to operate for nearly 900 years until it was closed by the Roman Emperor Justinian I in 529 AD.

Who was Plato’s most famous student?

Plato’s most famous student was Aristotle, who studied at the Academy for 20 years. Aristotle went on to found his own school, the Lyceum.

Does Plato’s Academy still exist?

While the original buildings of Plato’s Academy no longer stand, the site has been preserved as a historical area.

What is special about the Temple of Hephaestus?

The Temple of Hephaestus is one of the best-preserved ancient Greek temples. It is a remarkable example of Doric architecture and has remained largely intact since it was built between 460 and 420 BC.

Can you visit the Temple of Hephaestus?

Yes, you can visit the Temple of Hephaestus. It is located within the Ancient Agora of Athens.

How long does it take to see the Temple of Hephaestus?

Visiting the Temple of Hephaestus can take anywhere from 30 minutes to an hour.

What happened at the Temple of Hephaestus?

The Temple of Hephaestus was originally dedicated to Hephaestus and Athena Ergani. Over time, it was converted into a Christian church dedicated to Saint George Akamas.

Do you have to pay to see the Temple of Hephaestus?

Yes, there is an entrance fee to visit the Temple of Hephaestus as it is part of the Ancient Agora of Athens.

What is the significance of the Stoa of Attalos?

The Stoa of Attalos is a remarkable example of Hellenistic architecture. It served as a bustling marketplace and social hub in ancient Athens.

Is the Stoa of Attalos still standing?

Yes, the Stoa of Attalos was fully reconstructed between 1952 and 1956.

What was the purpose of the Stoa?

The Stoa of Attalos was a commercial center in ancient Athens, housing shops and providing a place for Athenians to gather.

Who destroyed the Stoa of Attalos?

The Stoa of Attalos was destroyed in 267 AD during an invasion by the Heruli.

What does ‘stoa’ mean in English?

“Stoa” refers to a covered walkway or portico in ancient Greek architecture.

Comments